-

What is gastroshiza (gastroschisis)?

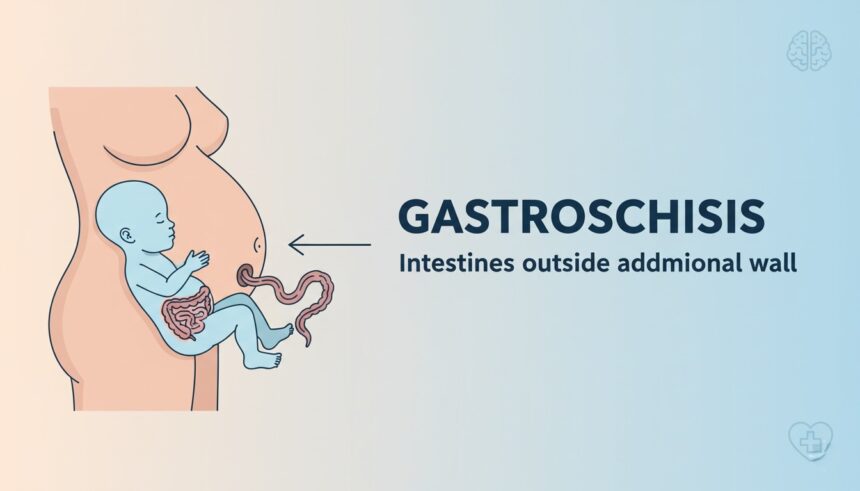

Gastroshiza — more commonly spelled gastroschisis in medical texts — is a congenital condition in which a baby’s abdominal wall doesn’t fully close before birth. Because of that small opening, loops of intestine (and sometimes other organs) sit outside the abdomen, exposed to the amniotic fluid rather than being covered by skin or a sac. That difference matters, since exposure can lead to swelling and irritation of the bowel.

When doctors explain this to parents, they usually show a diagram or an ultrasound image and use plain terms: “a small hole beside the belly button that lets the intestines come out.” Knowing the basic picture helps reduce fear — while the sight is alarming, the condition itself is well-understood by pediatric surgeons and neonatologists.

(Clinical note: gastroschisis is usually to the right of the umbilicus and lacks the membranous sac that distinguishes it from an omphalocele).

2. How common is it — who is affected?

Gastroschisis is uncommon but not rare. Population studies report an incidence roughly on the order of 1 in several thousand live births; rates have changed over time and vary by region. Younger maternal age shows a consistent association in many studies, and some environmental exposures have been investigated as possible risk factors.

What this means for an individual parent is simple: most pregnancies do not involve this condition, yet it is one of the congenital abdominal wall defects clinicians look for on routine prenatal scans. If a sonographer or doctor raises the possibility, the next step is usually targeted fetal imaging and counseling at a center with maternal–fetal medicine expertise.

3. What causes gastroshiza — what we know so far

Medical research has not pinned a single cause for gastroschisis. Current understanding favors developmental events in early embryogenesis — essentially, the abdominal wall fails to close properly as the embryo forms. Researchers have explored a mix of maternal factors and environmental exposures (for example, certain drug exposures and tobacco have shown associations in some studies), but no uniform genetic pattern explains most isolated cases.

For parents, that uncertainty can be frustrating. The important practical point is that doctors use what we know about timing and risk to guide testing and care — for instance, watching fetal growth and checking for other anomalies that would change counseling or management. When additional anomalies are not present, many clinicians view isolated gastroschisis as a condition with established, evidence-based treatment pathways.

4. How is gastroshiza detected before birth?

Ultrasound is the main tool. On a mid-pregnancy anatomy scan (commonly done around 18–22 weeks), a sonographer can see free-floating bowel loops outside the fetal abdomen — that finding is the hallmark of gastroschisis. Additionally, maternal blood testing (alpha-fetoprotein, or AFP) is often elevated when abdominal wall defects are present; it’s one piece of the broader screening picture.

If the ultrasound suggests gastroschisis, your care team may recommend more frequent growth scans and consultations with specialists (maternal-fetal medicine, pediatric surgery, neonatology). Those specialists will help explain what to expect at delivery and will plan immediate newborn care so the baby receives coordinated attention right after birth.

5. Preparing for delivery — location and team

One of the most practical things families can do after a prenatal diagnosis is plan where to deliver. Because babies with gastroschisis often require immediate neonatal stabilization and possibly surgery, delivery at a hospital with a high-level neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and pediatric surgical coverage is generally advised. This doesn’t always mean a cesarean section — many specialists support a trial of vaginal birth unless other issues require a different approach.

The delivery plan typically lists the team members who will be present: obstetricians experienced with fetal conditions, neonatologists, and pediatric surgeons. The team also prepares supplies to protect the exposed bowel at birth (sterile coverings, warming measures, IV access), so families can be reassured the first minutes of care are standardized and intentional.

6. Immediate newborn care — what happens in the first minutes and hours

At birth, the exposed intestines are handled gently and kept covered to limit fluid and heat loss and to reduce infection risk. A common immediate step is to place the lower half of the newborn into a sterile bag or protective covering — this shields the bowel and helps clinicians assess blood flow. Teams also place an orogastric tube to decompress the stomach, start IV fluids, and provide antibiotics as needed.

Stabilization aims to protect the baby while the surgical team determines the best approach for closing the abdominal defect. For many babies this means time in the NICU for monitoring, fluid and nutrition support (initially via IV/central lines), and careful evaluation of the intestines’ condition before any major operation. Survival, in modern centers with prompt care, is high — though the course may be longer for infants with complications such as bowel atresia or significant bowel inflammation.

7. Surgical options explained simply

Once your baby is stable and the intestines are protected, the next major step is surgical repair. Doctors aim to return the intestines to the abdomen and close the opening in a safe, controlled way. There are two main methods for this — primary closure and staged closure (using a silo).

In primary closure, the surgeon gently places the intestines back into the abdominal cavity and closes the opening in one procedure. This approach works best when the bowel isn’t too swollen and can fit comfortably inside. However, when swelling is severe or there’s not enough room inside the abdomen, the surgeon may use a silo — a sterile, soft pouch that holds the intestines outside the body for a few days. Each day, doctors slowly guide the intestines back in, giving the baby’s body time to adjust before the final closure.

Some hospitals also use sutureless closure, which lets the baby’s body naturally close the opening under a sterile dressing. This method can reduce scarring and sometimes speeds up recovery.

The choice of method depends on your baby’s condition, the size of the defect, and the bowel’s appearance. Parents are always part of the discussion, and surgeons explain each step before the procedure begins.

8. Possible complications and how they’re managed

Even with excellent care, some babies with gastroshiza can face complications — especially if the intestines have been irritated or damaged before birth. One of the most common challenges is bowel dysfunction, meaning digestion takes time to normalize. Babies may need nutrition through IV fluids (called total parenteral nutrition) until their intestines are ready to handle milk.

In some cases, small sections of bowel might be narrow, twisted, or blocked (intestinal atresia). If that happens, surgeons repair or remove the affected part during or after the main operation. Other possible concerns include infection, feeding difficulties, or slow weight gain in the early weeks.

The good news is that most of these issues can be managed effectively with close NICU monitoring, gentle feeding plans, and regular follow-ups with pediatric surgery and nutrition teams.

Parents should remember: progress in the NICU often feels slow, but each day usually brings steady improvement. Many infants go home healthy once they can feed by mouth and gain weight consistently.

9. Long-term outlook — what to expect after surgery

Most babies with gastroshiza recover fully and lead healthy lives. In fact, survival rates in modern neonatal centers exceed 90%, and long-term outcomes are excellent when managed early. Some children might experience mild digestive sensitivities or slower growth in the first year, but these usually resolve over time with proper nutrition and care.

Regular checkups are important during the first few years. Pediatricians watch for signs of feeding intolerance, hernia recurrence, or delayed growth. If the baby had a large defect or needed prolonged IV nutrition, the care team might also monitor liver function and nutrient absorption.

As your child grows, you can expect fewer medical visits and a completely normal lifestyle. Many children who were born with gastroshiza go on to thrive in school, sports, and daily life.

10. Support for families — emotional and practical help

Hearing that your baby has gastroshiza can be overwhelming, especially during pregnancy. Emotional support makes a real difference. Many hospitals now connect parents with social workers, psychologists, and parent support groups who have been through similar experiences. Talking to other parents who’ve navigated NICU care can ease fears and provide valuable insights.

For practical help, families often benefit from early planning — arranging time off work, preparing travel to a specialized hospital, and organizing home care for siblings if needed. After discharge, some parents join online communities dedicated to gastroshisis awareness or neonatal health. Reliable organizations (like the Gastroschisis Foundation and March of Dimes) offer educational materials, Q&A forums, and ongoing support networks.

Remember: seeking information from qualified healthcare providers and trusted medical resources (like NCBI or the CDC) is the safest way to stay informed.

11. Maternal care and prevention — what’s known

Research continues into why gastroschisis happens and whether certain maternal factors raise risk. So far, studies suggest an association with younger maternal age and possibly with some environmental factors, but no single cause explains most cases. Still, doctors encourage expectant mothers to follow standard prenatal health guidelines:

- Avoid smoking and alcohol.

- Attend regular prenatal appointments.

- Take recommended folic acid and vitamins.

- Maintain good nutrition and discuss any medication with your healthcare provider.

While these steps don’t guarantee prevention, they support healthy fetal development overall. Ongoing research aims to understand how nutrition, genetics, and environment interact to influence risk.

12. Practical checklist for parents

To help families feel more confident, here’s a simple list of questions to discuss with your healthcare team:

- Where should I deliver my baby, and what facilities are available there?

- How will my baby be stabilized immediately after birth?

- What are the surgical options and their recovery times?

- How long might my baby stay in the NICU?

- What signs should I watch for after surgery?

- Who can I contact if I notice any issues once we’re home?

- What kind of nutrition and feeding plan will my baby follow?

- Are there local or online support groups we can join?

Having these questions written down before each appointment can help you feel organized and informed. It also ensures you make the most of every discussion with doctors and nurses.

13. Conclusion

Gastroshiza (gastroschisis) may sound frightening at first, but understanding the condition and knowing what to expect can greatly reduce anxiety. Modern prenatal screening allows early detection, and advances in neonatal surgery have turned what was once a life-threatening defect into a highly treatable condition with strong outcomes.

Families play an essential role throughout the process — from prenatal planning to NICU care and home recovery. With guidance from experienced doctors, patience, and emotional support, most babies born with gastroshiza grow up healthy and active.

Trusting credible medical sources, staying informed, and connecting with supportive communities can make this journey more manageable and full of hope.